Article Originally published 3/17, 2021

via ManageMyWatershed.org (LINK)

Uh-oh! Alert! Water Depth Dropping!

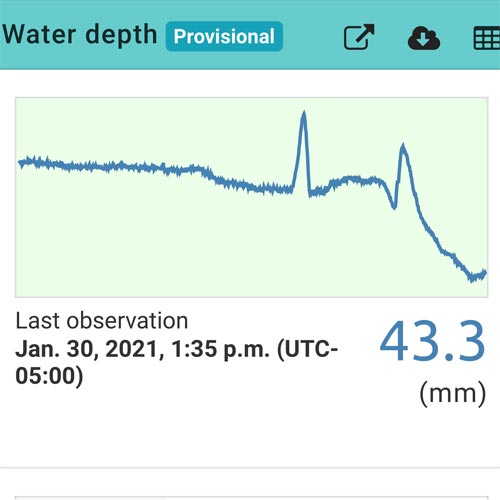

It is January 30, 2021, at 1:35 PM (UTC-5:00). In two hours, streamflow at Phillips Mill, Solebury Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, has dropped three inches in depth, from 4.7 to 1.7 inches (120 to 43.3 mm). The problem was clearly evident in the real-time data streaming to the Monitor My Watershed data portal.

It appears that the New Hope Crushed Stone and Lime Quarry outflow pump has failed again. Without a quick fix by the Department of Environmental Protection’s vendor, our feathered, fur, finned friends, and especially the macroinvertebrates below the quarry in Primrose Creek, are going to be under undue stress.

Above the quarry on a school campus, the stream faces other dewatering stressors from swallow and sinkholes that can reduce the flow to a trickle.

“It is alarming when sections of the creek run dry, and the bugs die.” So say students of environmental science teacher Phillis Arnold at the Solebury School. Primrose Creek runs right through their campus, affording science classes the opportunity of easy observation and access to water quality/pollution tolerance testing labs.

In addition to drastic creek water level changes, the students and staff are also aware of campus safety and ground collapse risk. The carbonate ground beneath the creek and their school has had a rapid rash of sinkholes and swallow holes twice in the last 21 months. These occurrences have accelerated as the quarry repeatedly (and illegally) exceeded the permitted mining depth by dewatering the groundwater during the previous two decades, putting the 2.7 square mile pocket watershed in severe duress.

A “Dewatering History” of Primrose Creek

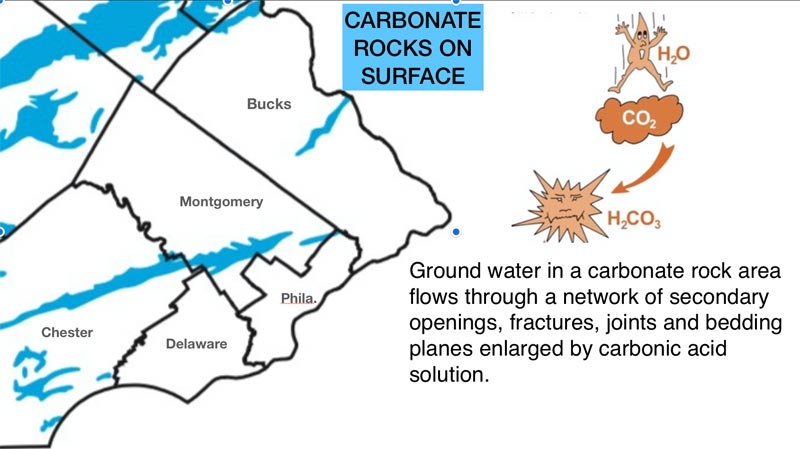

But first, a little history, a “dewatering history” that leads up to 2020’s problem of accelerated sink and swallow hole formation. Even before the 1700s, Bucks County farmers and builders had long been aware of the thin band of limestone and dolomite in a predominant red sandstone and shale area. These carbonate surface rocks extend from Doylestown to New Hope, Pennsylvania, along the Route 202 corridor. For hundreds of years, shallow rock mining had little effect on the area’s groundwater. In the 1900s, Primrose Creek was classified as a coldwater fishery and supported a population of native brown trout.

In 1926 the New Hope Crushed Stone and Lime Quarry opened and began operating with little noticeable environmental impact. It wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that mining efforts profoundly changed the creek’s continuity and the groundwater level, stressing the stream and impairing water depth in private wells. In 1992 the expanding quarry bisected the Primrose Creek’s stream bed. Continual electrical pumping of 500,000 gallons per day became essential to keep the quarry dry for mining and the Primrose’s downstream reach segment flowing. By 2008 quarry owners appealed to the DEP and began mining below the original depth limit mandated level of 120’ MSL (mean sea level).

Frequent formation of sinkholes and swallow holes became a noticeable problem on the Solebury School campus. Because of this danger, the Solebury School brought suit against the quarry and the DEP. The Pennsylvania Environmental Hearing Board (PEHB) ruled in favor of the school, citing “public nuisance” and “a serious safety hazard to township residents.” The PEHB condemned the DEP’s review and monitoring processes and fined the quarry $8,000. Sadly, these litigated findings and fines have had little effect on unscrupulous quarry mining and water pumping procedures in the years that followed.

By December 2020, the quarry had closed and was quickly put up for auction. For the community stakeholders, this ownership change increased the likelihood of property abandonment and certainly decreased the possibility for a quality restoration of the stream. It also did nothing to lower school and community anxiety about hazardous karst features like sink and swallow holes.

Five Questions About the Effects of Dewatering

This story covers the scope and sequence of four water-depth-changing events detected by EnviroDIY Monitoring Stations that led to successful mitigation of drastic flow changes in the Primrose Creek watershed from 2019 to 2021. It also begins to answer FIVE BIG QUESTIONS about the effects of dewatering by quarrying the Primrose watershed’s carbonate limestone rock.

- How can we monitor, detect, predict, and mitigate streamflow changes caused by carbonate rock quarrying?

- Why do swallow and sinkholes happen here so frequently?

- How safe is the school from subterranean collapses?

- What are the natural and anthropogenic causes?

- How can DIY monitoring be used to support action and litigation efforts in a watershed with quarry dewatering, sinkholes, and subterranean streamflow?

Six Resources for Measuring Susceptibility, Risk, and Mitigation of Stressors

Resource #1: Enviro-DIY Monitoring Stations

On May 1, 2018, Primrose Creek Watershed Association (PCWA) and Stroud Water Research Center installed two EnviroDIY Monitoring Stations on the banks of Primrose Creek, above and below the New Hope Crushed Stone and Lime Quarry in Solebury Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Our PCWA water quality monitoring team had prowled the creek for years with water testing kits in hand. To our delight, the SL-158 (Primrose Creek at Solebury School, aka “the School”) and SL-159 (Primrose Creek at Phillips Mill Community Association, aka “the Mill”) stations have become our most valuable assets in our community’s ongoing efforts to identify and mitigate the water depth stressors of Primrose Creek. They are our 24/7/365 eyes on the Primrose.

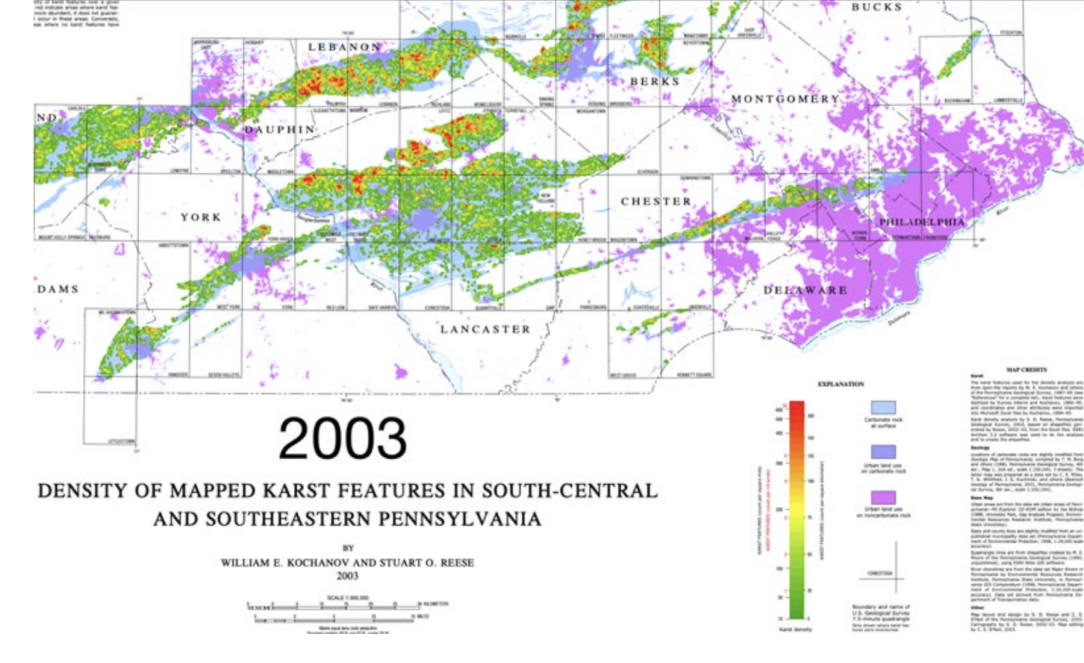

Resource #2: Karst Features Map

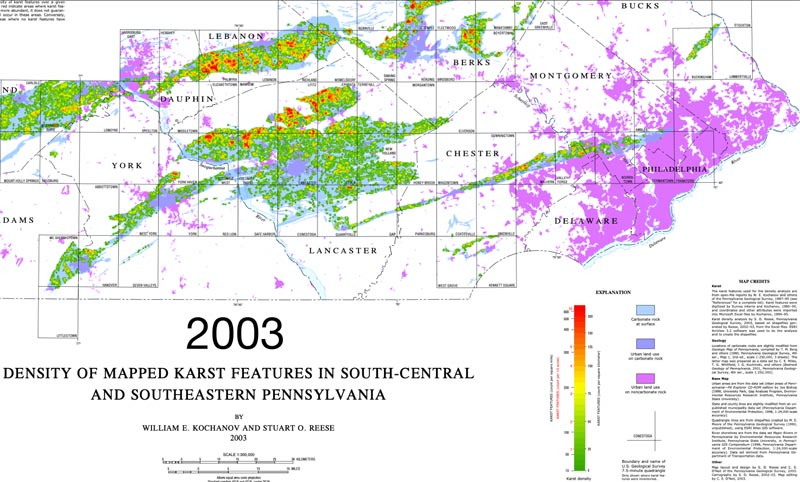

Density of Mapped Karst Features in South-Central and Southeastern Pennsylvania. William E. Kochanov and Stuart O. Reese. 2003. Publisher: Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Topographic & Geologic Survey, Harrisburg, PA, United States

The United States Geologic Survey maps carbonate rocks. This map displays GIS attributes of karst features (swallow and sinkholes) per 10 acres.

- What was the 2003 karst feature baseline count per 10 acres in the Primrose area? Three features/10 acres.

- What is the 2020 karst feature baseline count per 10 acres in the Primrose area? Eight features/10 acres.

Resource #3: Rockd App

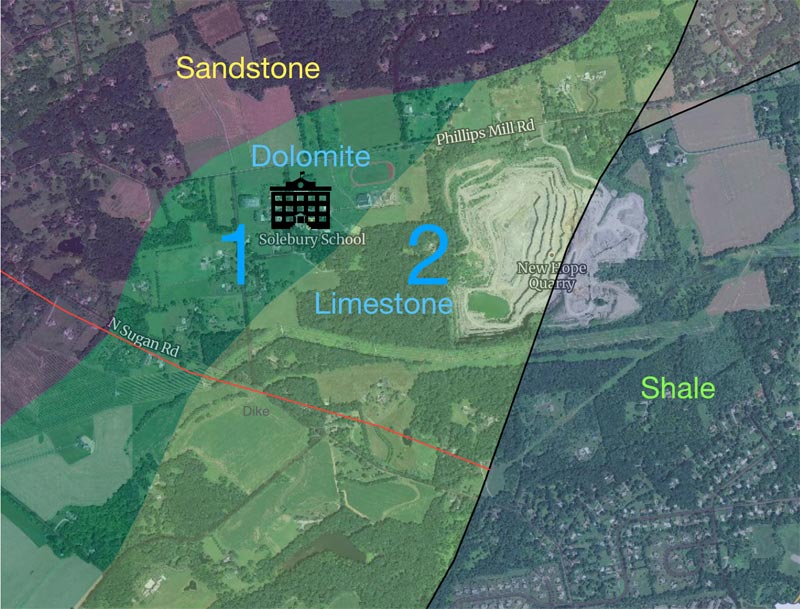

The Rockd app from the University of Wisconsin-Madison answers the question, “What type of rock is under me?” It is useful for Solebury Township residents and students who wish to see the extent of Primrose watershed’s affected carbonate rocks. Using the Rockd app overlay of the watershed, the extent of karst feature areas #1 dolomite and #2 limestone are displayed.

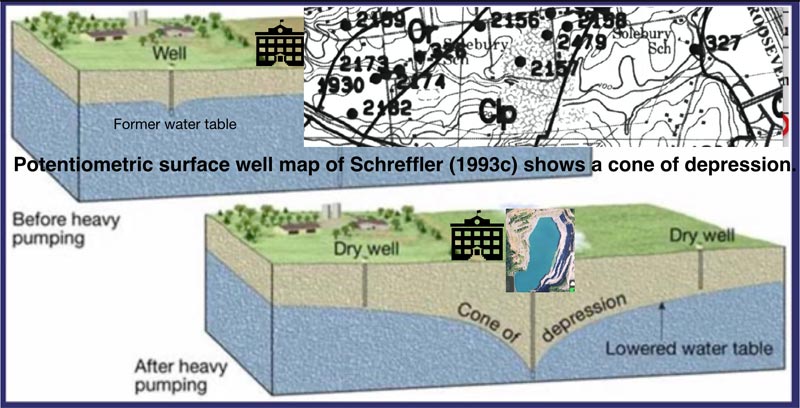

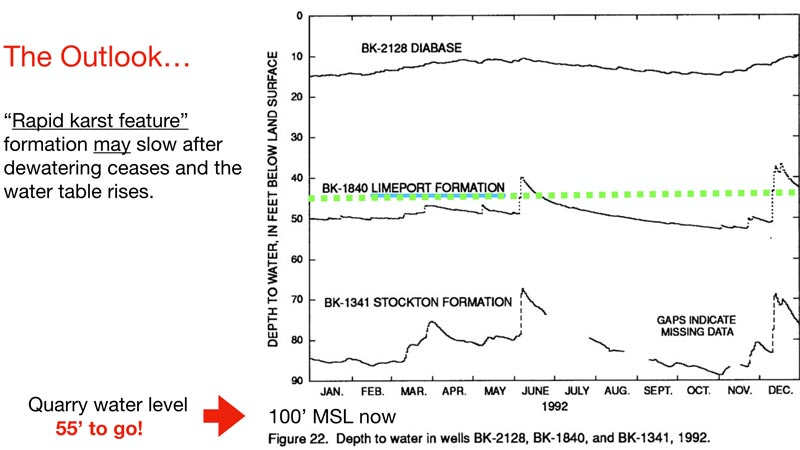

Resource #4: Potentiometric Surface Well Groundwater Cone of Depression Study, Schreffler 1993c

The potentiometric surface is the level to which water rises in a well. As you might expect, a potentiometric map is a contour map of the potentiometric surface. As on the earth’s surface, groundwater flows from high elevation, or potential, to low elevation.

The study documented the boundaries of the cone of groundwater depression around the quarry in an area approximately one mile long and 1/2 mile wide.

The Dewatering Events

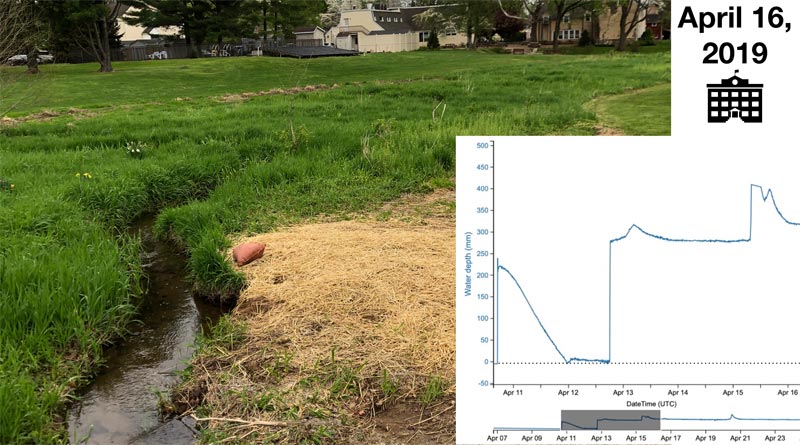

Event #1: Springtime Swallow Hole, April 12-14, 2019

Upstream above the quarry, the school monitoring station, SL-158, recorded a stream depth drop from 230 mm to 0 mm in 30 hours. The culprit was a 3-foot diameter swallow hole in the campus creek bed, 40 yards from a dormitory. School maintenance and safety personnel quickly cordoned off the area and, within a day, began a mitigation process.

On day #1 of remediation, the pirating swallow hole’s diameter grew to 10 feet from subterranean collapse and erosion despite heavy sandbagging. 70% of the creek’s flow was diverted underground. Sandbagging wasn’t working. An ambitious throat mitigation upgrade followed with a DEP guided plan that included tons of graded filter repair materials. Success! The creek’s mean depth stabilized. (Click on images to enlarge.)

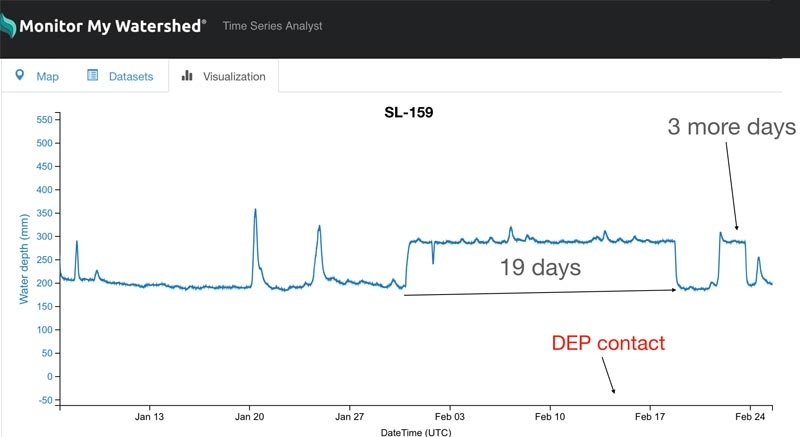

Event #2: 19 Days of Excessive Pumping, January 30-February 19, 2019

Unlawful pumping stressed the lower Primrose. For 19 days, scouring water eroded and washed out stream bank sections from the quarry’s piped outlet to the mouth at the Delaware River. The SL-159 monitoring station at Phillips Mill recorded the initial 19-day man-made deluge and an additional three days of intentional excessive pumping that took place after having contact with the DEP about the lack of the enforcement of pumping limits. Our watershed association suspects that this abusive pumping was done to facilitate harvesting high-grade stone from the quarry’s depths.

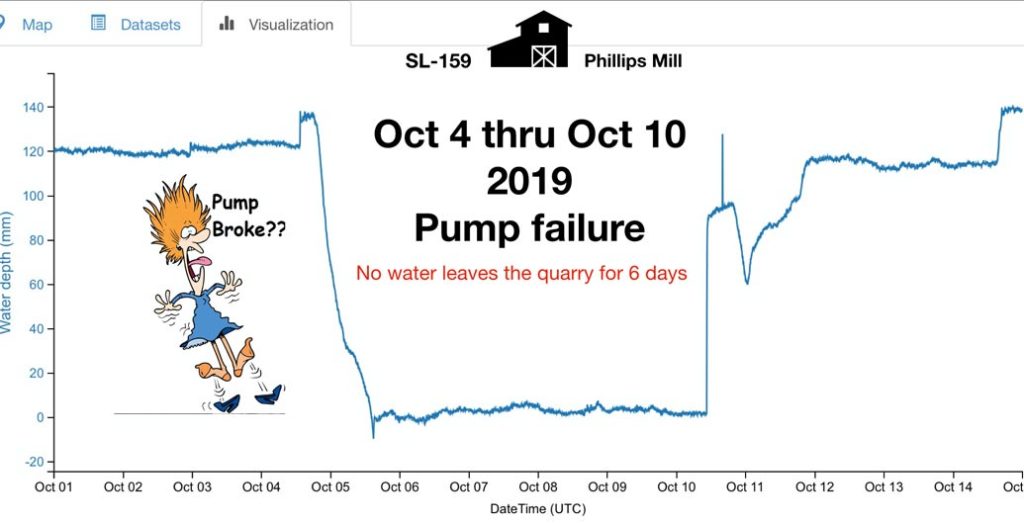

Event #3: 120 mm to 0 mm – Broken Quarry Pump, October 4-10, 2019

With a New Hope-Solebury High School PTI (pollution tolerance index) class field trip event scheduled for October 13, Primrose Creek suffered a severe 6-day dewatering event caused by a broken water pump. The entire lower reach below the quarry at the SL-159 monitoring station went dry.

Mercifully, cool temperatures coupled with an ample amount of moist leaf pack detritus saved the day for the resilient population of mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies. When the water began to flow again, the high school students tallied an impressive 27 point PTI stream evaluation.

Despite a DEP alert by PCWA, there were no warnings or fines levied by the DEP addressing the quarry owner’s tardy response.

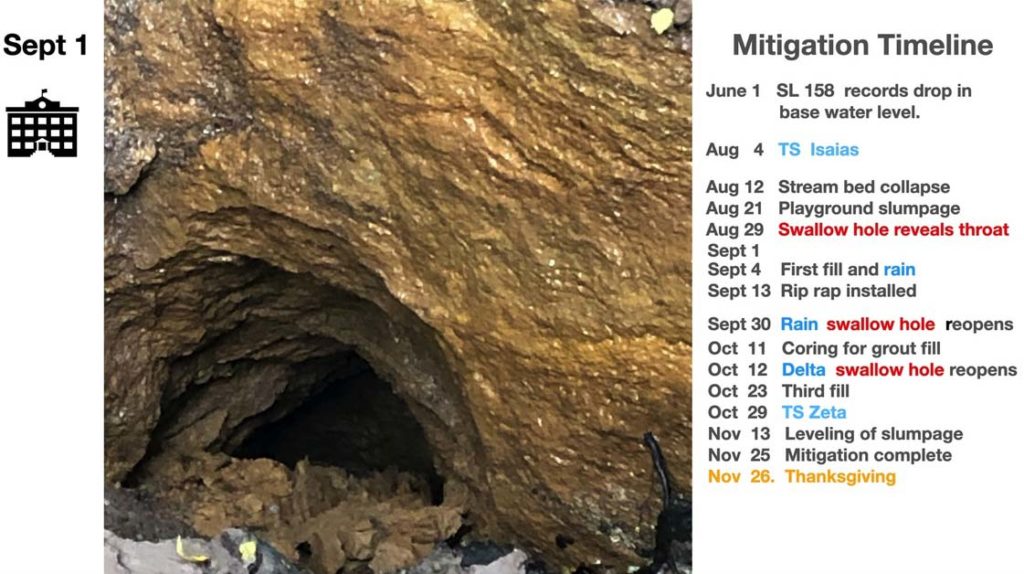

Event #4: Solebury Monster Swallow Hole, June 1-November 26, 2020

It is hard to believe, but the preceding three events were environmentally overshadowed by what occurred next to Primrose Creek.

Formation

There are a few ways to describe the cause of the flurry of sinkholes above the quarry:

“Frequent rain and drain.”

“Repeated acidic water in, dissolved carbonate rock out.”

“Incessant recharge of carbonic acidic water within a limestone dissolving cycle.”

The Monster Swallow Hole started in June 2020, but no one, including this author, took notice until after Tropical Storm Isaias’s deluge. On August 21, the stream bed’s bank and ground slumpage reached less than 10 feet from the Solebury School playground. It took 25 days for the depression zone to reach its maximum dimensions, 15 feet deep and 30 feet in circumference. On August 29, as the water drained, the swallow hole revealed its 3-foot diameter throat consuming 100% of the upper Primrose’s flow into the dolomite bedrock.

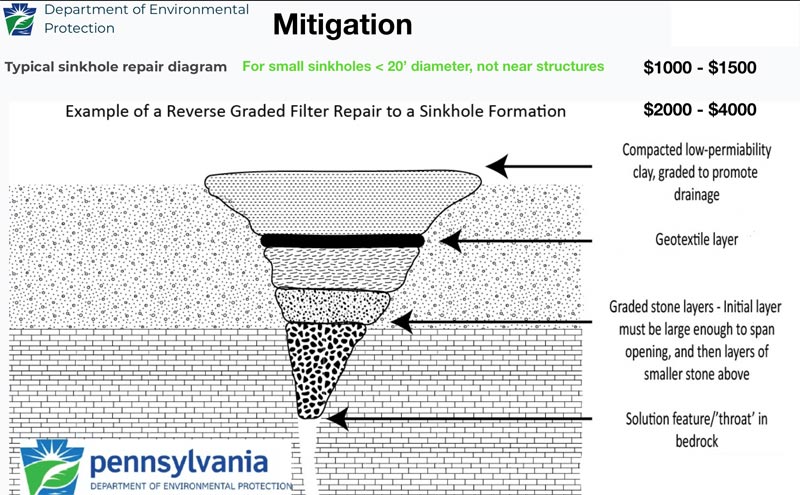

Mitigation

One week later, the school began remediation. Many loads of graded fill and poured concrete covered the throat and partially filled the stream bed. Sudden rains came with seven feet of fill to go. By the next day, the throat had reappeared and moved 15 feet downstream, continuing its thirsty and hungry earth slurry appetite. Wet conditions held up work, and on September 13, nine days later, more fill, concrete, and riprap rock restored the original stream bed level. That is until September 30, when rain reopened the swallow hole.

At this point, the school decided that campus danger was real, and their mitigation efforts were fruitless and frustrating. A professional grout compaction company was enlisted in early October. Preparation for grout compaction began with many exploratory stream corings. On October 11, a dozen cores were drilled. Voids were marked as they were located. Each void core site was flagged, and its 3” diameter opening was collared to prepare it for receiving pumped grout material. The next day, October 12, Tropical Depression Delta hit. The stream found a couple of collapsed collars and intruded the groundwork, reopening the swallow hole!

Work would not get underway again until decent dry conditions prevailed on October 23. The company applied a third graded-stone fill, and water-impaired corings were redrilled. By October 26, the pumping of the grout was completed. Tropical Storm Zeta struck on October 29, bringing with it a true hydrologic stress test to the continuity and soundness of the grout compaction efforts.

By November 13, observations showed that the mitigation held up to the storm’s might and a couple of smaller rain events. That only left some minor cosmetic stream bank bulldozing to build up and level the slumpage near the playground. This clean-up ended the work just in time for Thanksgiving. As of February 27, 2021, the Primrose’s upper reach has maintained its 200 mm mean base flow.

Litigation and Remuneration

“The Solebury Monster Swallow Hole” was the most water-consuming watershed dewatering event recorded by the SL-158 monitoring station. The draining of the Primrose’s upper reach started June 1, 2020, and lasted six months, decimating aquatic life and incurring the most extensive sinkhole remediation ($70,000 project) to date by the Solebury School. Getting mitigation reimbursement from the quarry owner is a difficult process. The Pennsylvania Environmental Hearing Board found that the quarry was liable for karst feature mitigation costs to residents. In the past, the owner was cooperative in fixing sinkholes while he was in business. With the quarry on the real estate block, the responsibility passes to the prospective future landowner.

The DEP does hold a $500,000 mitigation/restoration bond posted by the quarry. This money is earmarked for a future large project like a quarry water flow outlet structure that will reconnect, after 30 plus years, the upper and lower reaches of Primrose Creek.

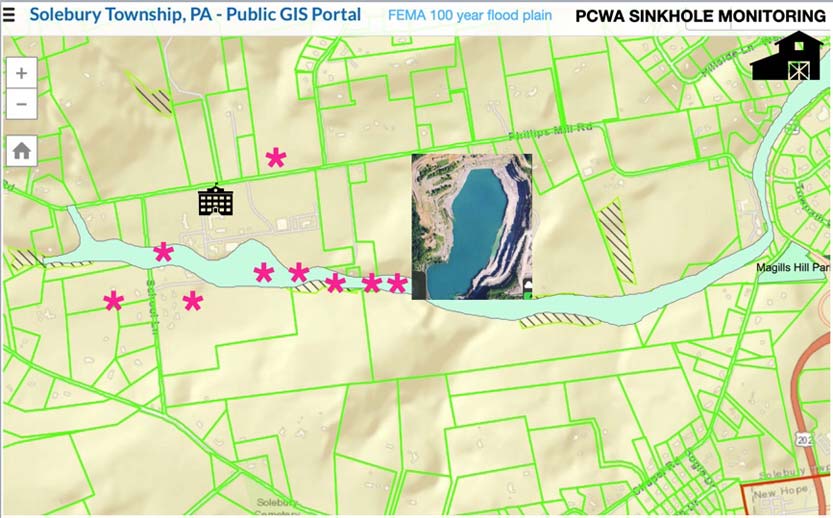

Resource #5: GIS

The story of the Monster Swallow Hole dewatering event incorporates topographic, geologic, hydrologic, and karst landform data. It is helpful to use a GIS-like spatial overlay to visualize what is needed to prepare the community for future sinkhole mitigation.

The purpose of GIS is to make query expressions easier to understand and analyze by organizing them in layers of geographical data. This is done by

- Projecting the future problematic area.

- Combining the Rockd app carbonate rock layer data under a GIS FEMA 100-year-old flood plain data layer.

- Adding the coordinates of swallow and sinkhole karst feature locations (marked with pink asterisks) onto the top layer. (Click on images to enlarge.)

Resource #6: People

The story continues as a support network from the Stroud Center, local schools, township supervisors, and a dedicated band of citizen scientists keeps PCWA focused on the goal of reducing stressors on Primrose Creek.

About the author: Francis Collins is the education and monitoring coordinator for Primrose Creek Watershed Association in Solebury Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

Comments 1

This article should be compulsory reading for the entire DEP, Solebury Township and Primrose watershed parcel owners